|

|||||||

Chris Evans was prompted by the picture of 'Humble' on the front of the summer 2004 edition of 'Boater' magazine to write of his experiences while working for the Golding brothers who ran her as an excursion boat in the 1950s and 1960s. Chris, who now lives in Germany, also recalls his adventures as a youngster on the river at Windsor.

I was born in Windsor in February '43 and was just a few years

old when I had my first boating experience on Thames waters.

I say Thames waters most decidedly because the actual venue was

Alma Road at Hoggs,

the grocer's store, where the road dips. (This area is now

the housing complex called Ward Royal.) Here the 1947 flood waters

lapped the tarmac and my older brother, David, and I launched

our boat which was nothing more than the zinc bathtub that we

used for our regular weekly bath in front of the living room

fire. We were not alone but surrounded by numerous other children

who were unable to go to school because of the flooding. They

could think of nothing better to do than to come and look at

the amazing spectacle of streets covered in a foot or so of water.

The junction of Alma Road and Oxford Road, Windsor.

Quite oblivious to any danger, we were quickly aboard our makeshift boat and with simple pieces of wood taken surreptitiously from our father's workshop to propel us, we were soon making steady progress into the 'everglades' of the Goswells, an area of terraced houses that no longer exists. The bathtub performed wonderfully in its dual role and our progress was without mishap.

Soon we heard a voice beckoning us from

a bedroom window of one of the terraced houses. A man and woman

were holding a basket that dangled on a piece of string. They

told us that they needed some provisions from the shop up the

road and asked us to get them. We readily agreed and almost immediately

other heads appeared at different windows with similar requests.

It was quite amazing just how much groceries one could pack into

that little bathtub but soon we returned resembling one of those

Sampans one sees in travel brochures welcoming cruise liners.

With a minimal fuss the goods were off-loaded with

the use of string and baskets and in gratitude we were showered

with coins. Our pals were extremely jealous and it was not surprising

that within hours there were several other tin boats plying the

flooded streets of Windsor. Needless to say, this surfeit of

craft depressed the grocery market.

We did not think much more about it until the weekend

when the local newspaper went on sale. In it was a picture of

my brother and me grinning from ear to ear in our bathtub boat.

When our mother saw it she went ballistic. Fortunately for me

her anger was directed upon my brother David, who being the senior

was expected to take care of me. [Editor: We are hoping to locate this picture -

can anyone help?? The edition would be dated late March 1947]

I remember in particular the lovely long

summer holidays when, with my older siblings ( I was the youngest

of eight children ), I would be sent off for the day with enough

food to ensure that we did not return until late afternoon. When

the days were warm and sunny the favourite place would be what

we called 'Sandy Bay' swimming baths. I believe its correct title

was 'The Windsor and Eton Swimming Society Baths' and was situated

in the side arm of the Thames that by-passes the Clewer Point

and passes under the Chinese bridge opposite the Racecourse on

the Buckinghamshire side. It was here that I learned to swim

at the tender age of eight. Within one summer I became a good

swimmer and consequently felt little fear of the water. I was

always fascinated by the many boats that were along the Windsor Promenade and inevitably I weaseled

my way into the employ of the Golding brothers.

The Golding brothers had been in business long enough

to recognize a willing helper when they saw one and I guess the

turning point of acceptance came after I was asked if I could

swim. '"Oh yes! Half a mile!" I declared proudly. A

wide-eyed nod of approval followed and from then on I was hooked.

The summer days simply flew past. There was always something

to do and I really loved to do it, be it scrubbing and baling

out the bilges, or the mad rush to collect all the cushions from

the rowing craft before the deluge of a summer storm. Then there

were the hilarious antics of people that would never be able

to row a boat as long as there was water in the river. The rewards

were minimal in monetary terms but in boating lore it was priceless.

The greatest reward was that rare grunt of approval that might

be accompanied with a big grizzly hand tousling my hair to signify

a job well done. I was also allowed the pick of all the boats

to take out at my leisure in the evenings when all work was done.

My favourite became the very lightweight Canadian canoe in which

I mastered the art of poling the way punts are poled. I have

to admit that I had a few duckings before I became capable of

racing the tourist river craft up to Boveney Lock and back, and

beating them.

These wonderful times were brought to a

rather sudden end in a couple of ways. My eldest brother, Michael,

was working for London Transport as a bus conductor. One day

he came home with the exciting news that the driver of his bus

had a cabin cruiser up on the Millstream at Clewer. Furthermore,

he wanted some repairs made to it, which Michael had undertaken

to do in exchange for being able to use it. And so it was arranged

that we three brothers would go there at the weekend and take

it for a run.

The cabin cruiser turned out to be a converted ex-army

25ft bridge pontoon with a devastatingly ugly box-like cabin

built on it and an aft cockpit with a converted Ford car petrol

engine as a means of propulsion. It is probably worth mentioning

that my older brothers had very little savvy about things nautical,

which probably explains their effervescent enthusiasm and my

sad disappointment. Enthusiasm led the way and it was not too

long before we had the engine burbling away as we threaded our

course out on to the mainstream where there is now the bridge

that carries the Windsor by-pass.

From here it was plain sailing all the way down to

the Donkey House pub just below Windsor and Eton Bridge. I vaguely

recall that the engine was overheating so it was decided to tie

up on the quay and go into the pub for a drink. I, being under

age, was left on duty to keep an eye on the boat. This I did

from the quayside and at a respectable distance so as not to

be readily associated with it. In due course my brothers returned

and after checking that the engine temperature was OK, the engine

was started and we set off for the return journey.

Being the utter novices they were, we had moored

up facing downstream and had to turn around. Michael was on the

helm and began the manoeuvre by turning in the direction of Romney

Island and the spit of land that protruded from it known as the

'Cobbler' (This has since been removed). It was clear that we

would not make the turn in one go, so reverse was selected with

the intention of making a three-pointer. Within a few seconds

the engine was brought to a shuddering and abrupt halt. One of

the aft lines had fouled the propeller. We still had forward

way and slowly drifted towards the Cobbler where I was able to

jump ashore and secure the boat.

There was much gnashing of teeth and probing with

the boat hook, all to no avail. However, my brothers are made

of clever stuff and a solution was quickly decided upon. I, unwillingly

stripped to my Y-fronts, and with the sharpest of the blunt knives

found in the galley plunged into the murky waters to remove the

rope around the propeller. It was not difficult, and the blunt

knife was not even necessary but, like my brothers, I too was

made of clever stuff and before I had finally declared the job

done - having surfaced a few times gasping desperately and indicating

that I could not go on - had wheedled a promise of a Knickerbocker

Glory ice-cream out of them as my due reward.

The engine was restarted and forward gear selected.

The boat surged forward and Michael urged David to push us away

from the bank. I was busy trying to pull my clothes back on to

my wet skin, there being no towel. Progress against the slight

current was noticeably slower especially at the bridge hole,

so the throttle was opened up a bit. I should mention that all

boat handling had been done by oldest brother, Michael, and any

request from yours truly to '' 'ave a go" had been

met with utter contempt.

David, being the most mechanically inclined of us

had now taken the engine cover off and was admiring the motor

set up. One would expect a sudden increase in engine noise but

such was the quality of build that it made little difference.

I stood close to Michael at the helm when there came a cry of

alarm from David.

"Blimey Mick, this exhaust is glowing red hot!"

"What?" Came the startled reply from Michael

as he dived down into the engine bay alongside David. They huddled

together in eager consultation while I craned over them to have

a look as well. Indeed the unconverted car exhaust manifold was

glowing a very attractive rosé colour. As we all considered

our options we became aware of shouting. It was getting louder

and more urgent, and what's more, it was directed at us. I looked

out of the windscreen and uttered something like "Oh my

God!" By which time Michael had sprung back to the helm

just in time to take control as the blunt ugly prow of this converted

bridge pontoon smashed into the elegant side of the most beautiful

boat on the river at that time, 'The Esperanza' (now known as

'Thames Esperanza').

Whilst we had been ogling

at this cherry red exhaust manifold the boat, unattended, had

made a slow turn to port and managed to smash fair and square

into the side of Esperanza as if guided there by GPS.

There was uproar! I was bitterly accused of being

the culprit by my brother Michael for not taking charge and looking

where we were going. However, being aged about twelve I do not

think that was a fair complaint. Certainly the Golding family

did not share Michael's position and were making it noisily clear

that he was held responsible. I kept below, which was a wise

move, because as it turned out none of the Golding family recognised

me or even realised that I was on board.

This became especially clear many years later when

I was employed as crew on 'Humble' and I was sitting on board

'Esperanza' next to 'young Odi' to make it look like there were

passengers on board and the boat would depart shortly. I sat

in one of the wicker chairs in the forward cockpit right next

to the repaired gunwale that had been damaged in that unfortunate

accident. Quite casually I said to Odi as I ran my finger over

the scarfed joint: "Did you do the repair, Odi?"

"What do you mean?", he replied.

"The repair after that boat rammed it."

"What do you know about that?", he asked.

"Well, it was my brother who was driving it",

I said.

His faced paled and his eyes looked sullen. We were

both silent for what seemed a long time and then he said quietly:

"Best that you don't say of word of this to anyone, especially

Jock."

The Golding brothers consisted of three brothers*

that I knew of. Eric operated the hire fleet of rowing boats

from the Eton bank, and I think was the youngest of them. He

was noticeable for his immaculate white naval type of peaked

cap and his equally pristine singlet vest, which he wore rain

or shine. Over the summer he soon gained an ebony tan and it

was said that if he ever took his vest off one would never know.

[ * February 2007. We are grateful to Terry Banham who writes: There were four brothers in the boat company 'Golding Brothers'. Two brothers, Harry and Alfred (Snowball), originally formed the company and the other two were Arthur and Frank (Jock). Mr Evans suggests that Jock was the son of Arthur but he was actually his brother. Editor, February 2007]

Arthur Golding, known as Big Odi, ran the

hire fleet from the Windsor side, but he was also the landlord

of the 'The Waterman's Arms' in Eton. He was a likeable, burly,

no messing, sort of chap with a voice like a sergeant major.

More than once I have regretfully stood in the way as he bellowed

at a wayward boater who cruised past too fast with too much wash.

He had three sons; one was 'young Odi' who had learned to be

a shipwright in the Royal Engineers and was a good boatbuilder

who taught me a few things over the years. Another, called Raymond,

would skipper 'Esperanza' each summer. He was a very quiet academic

sort of chap. I never saw anything of him in the winter and I

wonder if he returned to his profession of graphic artist at

that time. The third son was Jock, a small man whom I cannot

recall seeing laugh. Mind you, if you got a smile from him it

was as if the sun had come out on a rainy day. His son was called

Denis and he was more light hearted but could have sullen moods

at times. My enduring memory of Jock is when I had just pushed

a boat called 'The Angler' off the promenade. This was a similar

but smaller boat to 'Humble', skippered by Jack Lansley, who

was the young brother of the skipper of 'The Windsor Castle',

Harry Lansley. I perched myself in my usual position on the gunwale

and looked back to see Jock bending down to pick up a piece of

driftwood that had been trapped between 'The Angler' and the

promenade.

Such was the enterprise of this interesting family

that all drift wood was carefully removed and dumped up on the

grass verge that runs alongside the promenade. This would eventually

end up in their storage yard underneath the railway arches where

it would be cut up in time to be sold for firewood in the winter.

It was quite amazing just how much wood was accumulated in this

way. As we picked up speed and headed for another Boveney Lock

excursion I saw Jock slowly lose his balance and keel over into

the water - "Jock's fallen in the water!" I shouted

with unrestrained glee. Jack, the skipper, responded quickly

and shut down the throttle as he craned his neck to look back

in time to see Jock break surface with eyes as big as saucers.

He was quickly helped from the water by his son Denis and Big

Odi. With a grin Jack opened the throttle and we continued on

our way chuckling at Jock's misfortune.

When we returned from the trip I was standing beside

Jack when he inquired of Denis how Jock was. "He's OK",

came the reply, "but you should see the house - they've

got wet pound notes pinned up to dry all over the place.'"

I was sacked by Jock. It was a rather miserable wet

day and the fact that the little ball valve had worked itself

loose on the end of the old ex-Home Guard stirrup pump and plopped

into the river as I used it to prime the bilge pump on one of

the bigger boats, was probably just a bit too much for that day.

It was a rather non-event. I came to Jock holding up the pump

with the missing valve plain to see and he asked "What's

up", and I told him, and he just looked at me dolefully

and then , after a pause, said: "I don't think we need you

any more." "OK." I said putting the pump down

and walked off towards the bridge.

The next boat business was Charley Hill who had three

boats, I believe, and operated out of the Mill Stream at Clewer.

"Need any crew, Charley?"

"Sorry Chris, not just now. Maybe in a week

or so!"

"OK, Thanks."

Further on I met David Pickin, whose family owned

the Thames Hotel and Jacob's Boats. David asked why I no longer

worked for Golding's and I told him the whole story. "OK",

he said, "When do you want to start?" "Right now

if you like" I replied, and I did.

(actually registered the 'New Windsor Castle')

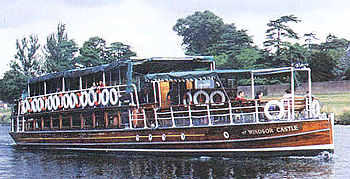

The fleet of Jacob's Boats at that time consisted of 'The Windsor Castle', 105 feet long and skippered by Harry Lansley, who knew how to handle this giant and make it look easy. His first mate was a muscular chap who I can only recall as Mick. Harry often depended upon Mick's skill and strength to hold the bows up with a pole when turning into the mooring at the Windsor promenade. When there was a downstream breeze we would sometimes hold our breath as Mick struggled with the pole while the breeze did its best to set the 'Castle' against the bridge buttresses. It never happened to my knowledge.

Note the funnel in her earlier, steam days

'The Empress of India' was about 80ft long.

A scaled up version of a popular gentleman's cabin river launch,

she had varnished top sides with a glass windowed aft cabin and

an awning covering the foredeck. Atop the cabin was an open deck

with seats. Right aft was a smaller deck with a small awning

over it. The skipper was Basil Davey and in due course I would

become his first mate.

Phil Bennett was the skipper of the next boat in

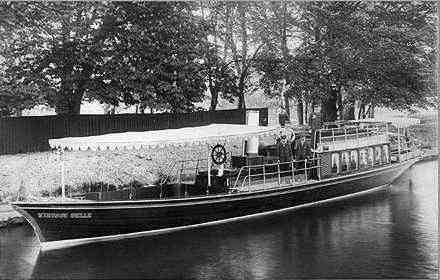

line, 'The Windsor Belle'. At around 60ft she was regarded as

being the best looking of the three large craft. I certainly

admired her delicate lines, but the suitably named 'Empress'

was my pick of the bunch. Phil was a small, wiry man who ruled

his ship with a very firm hand. I got along well with him but

I was glad not to be his crew.

Arthur Jacobs is seen standing on the upper deck.

Thanks to Catherine Pickin for this photograph

The bread and butter boats of the fleet

were five converted ex-navy harbour launches - at least that

is what I was told, but since then I noticed in the Autumn 2003

issue of The Boater a picture of 'Jeff' a Dunkirk Little Ship

owned by Michael Turk and described as a passenger vessel built

in 1923 by Joe Mears at Richmond. From what I can make out from

the picture I would swear that this boat was named 'Windsor Four'

and operated by Jacob's. There were five boats altogether of

similar size and construction and named 'Windsor One' through

to Five. The 'Four' was undoubtedly the best of the five, she

had a straighter and lower sheerline. She handled like a dream

with her single engine, which I believe was a six-cylinder petrol

/paraffin motor, and would stop on a sixpence as straight as

a die. The skipper then was a tall guy called Jim, who loved

a joke. On the 'Three' was a chap called Jack, and I was assigned

to 'Windsor One' with skipper, Bill Morgan. The other boats were

operated by family or by part-time skippers who came in when

needed.

Bill was only a handful of years older than my 17

(I reckon) and we got along well together, and established a

long-term friendship that endured until he took off for more

adventure in Australia. One of the silly things that sticks in

my mind is Bill's ability to lock his throat open and literally

pour a drink down. The funny thing was that he could never do

it in one gulp but always had to break it up into two gulps,

but nevertheless it was still impressive.

Bill would like to take bets on this ability. I had

only seen him do it with a half -pint bottle, so when he challenged

me that he could down a Coke in just two gulps I fetched a family-sized

bottle. When I returned his jaw dropped and he began to protest,

but this only made the others notice and so Bill's number was

called. With nothing to lose Bill took a deep breath and placing

the bottle to his lips upended it and gulped - then he gulped

again, and the bottle was empty!

Winter Work - 1960s

I stayed on for the winter, and when I

look back on that time I wonder just why I did. The wages were

poor and the work was mostly outside and in ghastly conditions.

The highlight was taking the three larger boats down to the tidal

waters of Chiswick, where the boats would be placed in a dry

dock for winter maintenance. The term dry dock must be taken

loosely, very loosely, because it was far from dry. The boats

would be let into the marina at a particular state of the tide

when a barrage would be lowered.

The mechanism for raising and lowering this concrete

affair was a mass of wire cables and multiple blocks. The driving

force was the remnants of a bull-nosed Morris motor car. Bereft

of wheels and most of the bodywork it rested on blocks and was

covered for most of the time with what looked like old coal sacks.

These would be removed when motive power was required, and after

priming the petrol pump, one of the yard men would swing the

brass handle protruding from below the trademark bull-nosed radiator

and the motor would clatter into life emitting clouds of vapour

from the upright exhaust pipe.

The boat to be dry docked would be positioned at

high water over the drying area, which was a bed of long beams

for the boat to come down on rather like a tidal scrubbing-off

dock. As the tide receded the boat would be lowered onto the

beams. It was nerve-racking stuff because there was no immediate

way of stopping the progress. If anything went wrong you could

do nothing until the tide returned more than 12 hours later.

Before dry docking 'The Windsor Castle' we had to

remove the many one- hundredweight blocks of concrete from her

bilge. I do not recall how many exactly, but it must have been

about one hundred. The system was simple enough; two people would

slip a cut-down scaffold pole through the two rings in the top

of the block and then carry it out and up on to the dockside.

When the boat was recommissioned all these blocks would have

to go back.

The trip down was exciting for me, with a real sense

of going into foreign waters - not just foreign but tidal. But

that was the easy bit. The real fun started after the boats were

settled on their dry dock and ready for scrubbing. We had no

pressure washers in those days and it was a case of getting down

and under the boat in a space about 2 ft high. It seemed a never-ending

job wriggling on your back between the beams and scrubbing away

with a stiff brush and a bucket of water. Every now and then

one of the skippers would come along and hose down the area you

had just done and comment on whether it was OK or needed more

work. Fortunately much of the working day was taken up with travelling,

so the actual time underneath was not long enough to make it

unbearable. But it did seem to go on for ever. When we had finished

scrubbing off it was time to paint the bottom with bitumen. Oh

what a mess!

Other winter work took place on the island immediately

downstream of Swimmers Eyot, which I believe is called Band Island.

This provided moorings on piles for the boats and also bore a

ramshackle wooden workshop of generous size long since demolished.

Access to the island was via an old working punt tethered with

a weighted line that would pull it away from the promenade at

night to discourage unwanted visitors.

There was a small slipway on the upstream end of

the island where an old chap would sit to eat his lunch and share

a few tit bits with the odd mallard duck. The ducks became so

familiar with him that they would eat from his hand. It was very

close to Christmas when I heard the familiar call from the slipway:

"Here, ducky duck duck. Here, ducky duck duck" And

as I rounded the corner I saw the man crouched down at the water's

edge offering a crust of bread to duck, while behind his back

he wielded a club-like balk of wood.

Beside the slipway lay the dried out hulk of the

wooden boat 'Sybarite'. Apart from gaps in the carvel planking

that were wide enough to drop pennies through, she did not look

too bad. I liked what I could make out of her typical river launch

lines and wondered why she was just left to rot. I was told that

she was too small for commercial usefulness. I do not think she

had an engine in her then but there was a long prop shaft with

many grease pots along its length.

Sometime later Mr Arthur Picking related a tale

about her as we sat on one of the tourist boats trying to coax

passengers on board. He was skippering 'Sybarite' without a crew

and there was not much business at the time. The few passengers

aboard were sitting forward so that as the boat cruised up to

Boveney Lock he decided to lift the rear floor boards and give

the grease pots a turn or two. This would have been way back

in the 'thirties, I guess, and the fashion was to sport a very

long multicoloured scarf that would twine around the neck twice

and then almost touch the floor. Mr Arthur (as we all addressed

him) sported such a scarf and as he bent down to give the grease

pots a turn, one end of the scarf snagged onto the spinning shaft.

In Arthur's own words: "My god! it all happened

so suddenly and yet there was something like slow motion about

it. It snatched at my neck and tightened so much I could not

breathe or even cry out. It started to pull me down towards that

spinning shaft. I could not reach the controls, I was just seeing

that spinning shaft! In one desperate moment I grabbed the snagged

scarf with both hands as tightly as I could and with all my strength

and weight threw myself backwards. The scarf broke and I lurched

so far back that I almost toppled over the side.

All the deck seats and the furniture out of the saloons

of the three larger craft were placed in the boathouse. Each

year the saloon tables had to be carefully rubbed down with wire

wool and several coats of varnish added. Quality control was

undertaken by the skipper of the boat whose tables were being

varnished, and that quality was first class. After rubbing down

with wire wool the table would be carefully washed with clear

water and then dried with a chamois leather. These wash leathers

would pick up the fine dust and had to be cleaned regularly.

That was one job I hated. I would be dispatched to the river

edge with a bucket full of maybe a dozen leathers to be thoroughly

cleaned. This entailed steeping the leather in the river water

and squeezing the water through them until there was no cloudiness

in the water. In mid winter, with the temperature of the water

just a few degrees above freezing, it was uncomfortable to say

the least. I particularly dreaded the test by Phil Bennett, skipper

of 'The Windsor Belle' who would take one of the 'cleaned' leathers

and immerse it in clean water and then squeeze it out. Any cloudiness

and it was back to the water's edge to do them all again.

The old workshop was without electricity and there

were many gaps to allow draughts through. If you complained of

being cold you were told to work harder. The actual varnishing

of the tables would take place in the spring when air temperatures

had risen somewhat and would aid drying. It was a time fraught

with anxiety and short tempers. Some skippers became paranoid

that their tables were not getting fair treatment. And woe to

any unsuspecting soul who happened to allow a strong gust of

wind that might stir up dust to enter .

With the spring came the promise of another summer

season and the activity on the island became frantic. There were

seats to be loaded on to the upper decks. Tables to be screwed

into place in the elegant saloons. Awnings to be dragged out

from the loft and designated to the correct boat for fitting.

The last-minute touches would be scrubbing the laid teak decks

and then shining the brass fittings with wire wool.

So passed the seasons and the years. I probably

spent four continuous years working on the waterfront and loved

it all. But family and friends would warn me that it was a dead

end job and I should look to a more enduring profession. I guess

their concern did get to me, though I showed little signs of

that at the time. Being the son of a carpenter, I had started

my apprenticeship early in life and was capable of doing a carpenter's

job at the age most youngsters start to work. The knowledge that

I had this capability allowed me the freedom to enjoy those younger

years when the rewards were more spiritual than material. Indeed,

as I look back on my life, those times were very rewarding and

a marvellous stepping stone to adventure. Because I was a capable

crew I was often asked to take a privately owned boat down to

tidal waters. This developed into trips to France or the Channel

Ports, and gave me the chance to learn navigation and pilotage.

It eventually led to a post as professional skipper on a magnificent

Morgan Giles 45 express cruiser, which I cruised quite extensively

from the Baltic to the Bay of Biscay.

I remember one family I met in the Donkey House pub

at Windsor, where I used play guitar and sing. The father and

son were fine musicians and when they heard me one night they

went off to fetch their instruments and we had a wonderful session.

I quickly learned that they were on holiday with a newly acquired

converted ex-naval harbour launch. It was about 50 ft long with

a 100 h.p. Perkins single engine. The father, Nick, complained

that the craft was bewitched because every time he took it into

a lock it would suddenly slew across the basin diagonally at

the last minute. I tried to explain that it was the 'Paddle wheel'

effect of the large propeller, but he insisted that it was far

more complicated and we ended up betting a crate of beer that

I could not take it into a lock and keep it straight. After fifteen

minutes practice we entered Romney Lock. I won hands down. Poor

old Nick, he could hardly believe it, but he paid up and helped

to down the prize too.

From that meeting we later made a six-week cruise

to Normandy and St Malo, Brittany, which culminated in a sail

up the Thames through the middle of the celebrations to commemorate

the Great Fire of London. Perhaps the most profitable skill I

developed from those years was that of learning to project my

voice over a distance through touting for customers. This helped

me in my hobby as a singer-guitarist and even more so when I

turned professional in the early 'eighties and enjoyed a career

entertaining throughout Europe. I have now retired and settled

down with my German-born wife in Southern Germany. But many ties

with Britain remain, and, of course, my love for the Thames.

I make frequent trips to England, and there will probably be

even more now that I have bought 'La Petite Souris', a James

Taylor cabin cruiser. I look forward to bringing her along to

a Thames Trad Rally.

'Robin' writes of his Memories on the Thames at Windsor

Having read Chris Evans's article above 'Robin' sent us the following emails

What a surprise! I chanced across the

page in which Chris Evans writes about his childhood memories

of the Thames at Windsor. The Golding brothers (Snowball and

Jock) took me under their wing in 1942 when I was 12. My name

is not Robin but that is what they all called me. I spent all

my spare time by their "Box" headquarters on the Brocas

during the summer and paid occasional visits to their railway

arch workshop during the winter. [The 'box' was a small shed with an opening side

erected on the Brocas. I believe that oars were stored in the

'box' at night and offered some shelter when customers were few

and far between on wet days. Editor.]

Soon after I got to know Snowball he got a

wave from Jock on the Windsor side of the river to indicate that

he had a customer to hire a boat. Snowball asked me whether

I could row and I replied "Yes" although I never had

rowed - well, it looked quite easy! Snowball then asked me to

take a boat over to Jock. All went well and my rowing days had

begun.

When elderly or disabled people wanted to go

out in a boat I was often allowed to do the rowing. The customers

were charged double for this service, 5/-, of which I was given

half a crown. [5/-

Five shillings or a 'crown', 25p in today's money. Half a crown

is therefore 2/6, two shillings and sixpence, or 12.5p. Editor]

Sometimes I was allowed to use a punt to ferry

people across the river. Less often I was allowed to row people

up to the race course. The drill on these occasions was "Collect

the fares well before landing".

If business was a bit slack I was often allowed

to take a boat out on my own. As a smallish boy my favourite

boat was Poppy (No. 13?), I wonder if Poppy survived to Chris

Evans's 'Golding Era'.

I also recall that another Golding brother,

Arthur, who did not do anything with boats although he was the

landlord of The Waterman's Arms in Brocas Street behind the Eton

boathouses.

I knew Arthur and Raymond but I did not realise

that Arthur did anything with the Golding fleet. Jock seemed

to be commander of the Windsor side. Perhaps this was something

that Arthur took up later. Also, in my time, Raymond seemed

to have very little to do with boats.

There was a non-Golding member of the team,

an older man called Josh. He was largely involved with boat

maintenance if I recall correctly.

As an evacuee from Eastbourne, my 'Golding

Era', which lasted until the end of the war, was one of the happiest

times of my life.

I am so happy that Chris Evans enjoyed his

time with the Goldings.

'Robin'

Our thanks to both Chris

and 'Robin' for their memories. Do you have any memories to share,

or some pictures? We would be delighted to receive them.