|

The Tapestry Manufactory began with four low warp looms,

by 1882 there were eight looms and at the closure in 1890 there

were sixteen. One high warp loom was purchased for experimental

purposes, and for comparison of work. It appears to be significant

that American tapestry works established in 1893 after the Windsor

works had closed were all low warp, thus following the trend

established at Old Windsor and no doubt taken to the United States

by the same weavers either direct or from Aubusson. It is known

that one of the first families of weavers to go to America, the

Foussadiers, took with them a small portable low warp loom. This

was perhaps the walnut one used to demonstrate the technique

in the Guildhall at Windsor during the exhibition of Windsor

tapestries in December 1878, where it was used to weave the panel

presented to the Borough by Henri C. J. Henry.

One of a pair of

Commemorative Banners presented by Mr H Henry to the Corporation

of Windsor on June 20th 1887.

Designs for the Tapestries

The notable Victorian historical

artist, E. M. Ward R.A., who lived nearby in the Borough of Windsor

and who was a friend of several members of the Royal family,

was one of the first artists engaged to prepare designs and cartoons

for the new Windsor Tapestry Manufactory. Between 1876 and his

death in 1879 he produced several designs for tapestries for

the staircase of the eccentric Christopher Sykes M.P., whose

new mansion in Hill Street, Mayfair, was where he entertained

the Prince of Wales, later to become King Edward VII. These pieces

were of hunting scenes in medieval times. Ward also designed

the huge 'Battle of Aylesford' tapestry - the largest ever made

at the Windsor works. His widow, Mrs. Henrietta Ward, worked

on several cartoons after his death.

In 1877 the first major series of tapestries - the eight panels

of the 'Merry Wives of Windsor' designed by T. W. Hay (an associate

of Henry's at Gillows) - were ordered by Gillows for the decoration

of the Prince of Wales Pavilion at the 1878 Paris Exhibition.

Here they hung in the dining room. They were very good - good

enough to win the Gold Medal for tapestries against the competition

of the great French manufacturies, a remarkable effort for a

new works. During the research for The Royal Windsor Tapestry

Manufactory in 1979, these tapestries could not be traced, but

just as the original printed version of this history was going

to press, seven of the eight came to Messrs. Christie for auction

and with their kind permission could be examined and photographed.

In addition, there have survived sketches for the 'Merry Wives

of Windsor' together with the mantlepiece they flanked, which

contained the tapestry portrait of the Queen illustrated above.

This mantlepiece, inlaid with ebony and ivory and richly carved,

and the gold medal tapestries, were subsequently bought by the

millionaire Sir Albert Sassoon for his mansion at 25 Kensington

Gore, where the Prince of Wales was a frequent guest.

Few of the original designs or cartoons are known to have survived.

Of the four cartoons for the historic Royal Windsor tapestries

in the Mansion House, three were destroyed in the 1941 blitz

on London. Several of the cartoons for the 'Royal Residence'

series of tapestries which hung above the Exit stairs from the

State Apartments at Windsor Castle are listed in the Catalogue

of Prints and Drawings at the Victoria and Albert Museum, but

do not now seem to be there. The pair of cartoons for Queen Victoria's sofa, also listed, are still safe,

as is the cartoon for Prince Leopold's

Arms. It is possible

that the sofa survives in the royal collection but the tapestry

for Prince Leopold's Arms is one of many that cannot be traced.

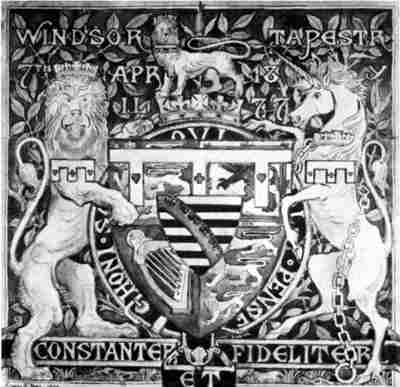

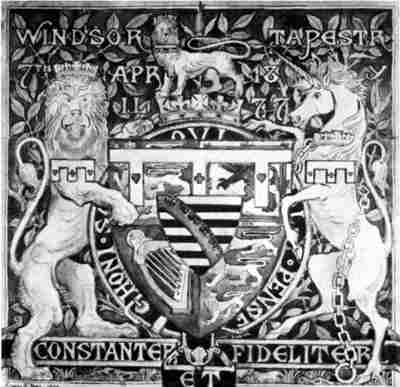

Prince Leopold's

Arms

Prince Leopold's

Arms

Chalk designs by Richard Beavis and E. M. Ward for the horses

and figures in Ward's huge 'Battle of Aylesford' tapestry are

on loan to the museum at the Guildhall, Windsor, from the Maidstone

Museum, together with the watercolours for this work and the

one by J. E. Hodgson R.A. for his 'Men of Kent marching in front

of Harold's Army'.

The Manufacture of the

Tapestries

The wool was obtained in

the natural colour, and dyed in copper vats to match exactly

the colours in the cartoons. The vats at Old Windsor were first

established by Brignolas in an outhouse at the 'Lord Nelson'

public house and soon moved to Manor Lodge, Straight Road, Old

Windsor. Outhouse and Lodge are now both demolished. The latter

site adjoins the still existing Manor Cottage and has associations

with both the Tapestry Works and the Royal Windsor Stained Glass

Works which was contemporary with the tapestry manufactory, but

under separate management.

Thousands of shades were prepared, and by twisting lighter or

darker shades of wool in one or two of the three strands, a range

of colours could be obtained to match the slightest change of

tint. Vegetable dyes were used, aniline dyes apparently being

spurned by the dyers, and these dyes with their mordants were

the responsibility of the Head Dyer, first Brignolas, then Jean

Foussadier. Foussadier apparently found the Old Windsor water

just as peculiarly suitable for dyeing as that of the Bievre

at the Gobelins in the parish of Saint Marcel near Paris. Later

he was to find the waters of the Bronx River in New York just

as suitable, 'by reason of the dissolved vegetable content'.

Here he taught all he knew to his younger son Louis, who was

to succeed his father as manager in New York, 32 years after

his arrival and apprenticeship there.

The traditional natural dyes were no doubt used, those that had

proved resistant to light. Indigo had replaced woad for blue;

a warm red came from madder and red also came from dried insects

known as Kermes, and from cochineal and Brazilwood. Purples were

made from the orchilis lichen, and the various mordants available

together with blending, gave a wide range of colours.

Shading and hatching (hachures) were used to convey three dimensional

form, folds in draperies and even skin tones and contours, together

with subtle blends of colours and highlights. In 1877 Brignolas

recorded that 5,000 shades had been produced for the work in

progress which included the Queen's portrait, and 'The Merry

Wives of Windsor'.

Brignolas was enthusiastic about the range of colours - the Circle

Chromatique - that had been developed by M. Chevreuil, who was

in charge of the dyeing laboratory at the Gobelins. This was

because of the possibilities for imitatating painting, but in

the opinion of many, including William Morris, this set the art

on a fatal course, and depreciated the tapestries' artistic integrity.

However, the portrait of Queen Victoria had very many admirers,

even Ward, who agreed with Lord Ronald Gower that 'it was faithful

to the original, and with perhaps a little more life... '

Changes of colour break the interlacing of the weft, and if continued

for several rows, becomes a slit. These, unless very small, have

to be sewn up after removal from the loom. The interlocking of

wefts obviated slits, but slits were sometimes required to indicate

a definite division, or shadow. Texture was given by 'packing'

or building up the wefts and by eccentric weaving. Slits were

sewn up by Mme. Foussadier and her daughter, Mlle. Adrienne.

The Windsor looms were 'basse-lisse', horizontal or 'low-warp',

and not 'haute-lisse', upright or 'high-warp', as at the Gobelins.

The weavers sat at the low-warp looms - as many as there were

room for having regard to the design and urgency. The operation

of the pedals enabled the bobbins loaded with coloured thread

to be passed in alternate directions. A supplement dated 29 April

1882 to the Illustrated London News contains a page of sketches

of work in progress

at the Royal Windsor Tapestry Manufactory: 'Dyeing the wool,'

'Winding the wool', A low-warp Tapestry loom, Preparing the warp,

plus an illustration of several women engaged upon repairing

old tapestry. Mme. Foussadier and her daughter Adrienne were

the chief needleworkers and repairers at Windsor and, after 1893,

in New York.

The repair of old tapestries is one of the important jobs that

comes to a tapestry works, and is extremely skilled. Queen Victoria

ordered that tapestries from Holyrood House should be sent to

Windsor for repair at the works, as were tapestries from Inverary

Castle sent in 1877 after a disastrous fire. After a similar

fire in 1975 the same tapestries were sent to nearby Hampton

Court for repair. The Irish House of Lords' tapestries were also

sent to Old Windsor for repair in 1878 and it is ironical that

when such work was desperately needed to keep the work force

employed in 1885, especially those women with parents to support,

excuses were found to deny the order to Old Windsor for repairing

some Hampton Court tapestries. Instead it was decided to employ

darning women unused to tapestry repairwork, rather than give

the struggling Royal Windsor tapestry works the chance to earn

some money. The Queen's wish that the work should be given to

Old Windsor was ignored, and the workers' expertise in repair

was denigrated. This was not the first time that the project

had met opposition - the 'trade' aspect together with the financial

uncertainty of which may have been unpopular in certain high

places.

When work was waiting and orders plentiful, many weavers came

to Old Windsor attracted by the good wages - 10 old pennies an

hour, £1 for 24 hours' work. In 1877 power-loom weavers

were getting only 87pennies. Before decimalisation in the UK

the pound sterling comprised 240 pennies. There were 12 pennies

in a shilling (5p), and twenty shillings in a pound. Spinners

received £1.69 per week according to Mr. Roy Assersohn,

the City Editor of the Daily Express in its 23 December 1977

issue. The working day at the Windsor Tapestry Manufactory commenced

at 8a.m. and finished at 6.30p.m. Most of the workers lived in

the village, providing for themselves. Eventually there were

100 households attached to the Manufactory and as many collections

of household furniture. Apparently the household effects were

found by the Manufactory, so that there were 100 sets for disposal

at the closing down sale by auction in 1895.

The weavers taught English apprentices, but there were French

apprentices such as Jean Foussadier's eldest son Antoine, who

had earned the designation of weaver by the time the Old Windsor

works had closed. Foussadier Census entry. He is on record as having worked on several important

tapestries including the Aldenham Tapestries by Herbert Bone.

Some apprentices went to the Merton Abbey tapestry works started

by William Morris. These included William Haines and William

Eleman. Both were highly regarded there and given important work.

Another weaver from Old Windsor - Octave Dennaud Bouret - was

to find employment at the Edgwater Tapestry Looms (1913-1932/3)

founded in the New Jersey town by Lorentz Kleiser. Later he went

with Kleiser to Palos Verdes and Hawthorne, California, in the

1930s in an attempt to continue the tapestry enterprise, then

suffering in the Depression.

Other weavers whose names are known include J. Roby, J. Brunaud

and J. Bregere. These three also worked on the Royal Windsor

tapestries for Aldenham House, Herts. Another worker named Francellon

had a young daughter Antoinette who at the age of three was to

present Prince Leopold's bride with a bouquet as the wedding

coach stopped briefly at the works on its way to Claremont in

April 1882.

Politics and weaving have never been far apart. English wool

played an important part in the social and economic history of

the Middle Ages, when cloth from English wool woven in the cloth

towns of Flanders supplied the traders of Europe. Edward III

made great efforts to establish the manufacture of woollen textiles

in England using wool denied to Flanders. He was aided in this

by the repression and persecution of the Flanders workers which

resulted in their coming to England where conditions appeared

to be better.

Similarly in the revolutionary days of the Commune, French tapestry

workers were attracted in 1876 to the newly set up looms of Windsor.

Michel Brignolas was an emigre who had fled from the Commune

and he probably was instrumental in inviting other experienced

workers to make the journey from Aubusson, France, to Windsor - more

than 500 miles - but the pay and conditions were better than in

France.

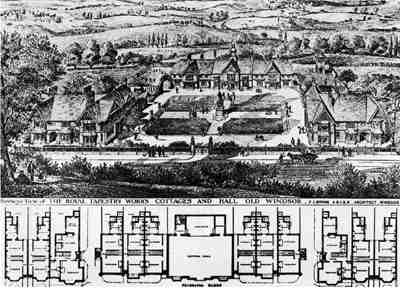

In February 1877 there were six workers engaged in weaving new

tapestry and repairing old at Manor Lodge. This was a small two-storey

building opposite the present 'Tapestries' or Tapestry Hall.

The latter was built in 1882 to house the expanding manufactory

and included twelve cottages for employees. A large central hall

was provided with a gallery for the display of finished tapestries.

The site for this building was leased with difficulty after long

delays from the Crown, possibly only after pressure by the Queen

and after the success at the 1878 Paris Exhibition. There had

been considerable obstruction by some at Court, who appeared

to fear a large satanic mill would develop, with smoke and noise

to distress the Castle. Prince Leopold's interest in the project

was deprecated and the Queen's support nullified for a long period.

In 1828 Windsor's first gasworks had been proposed to be erected

at 'The Nelson' public house, Old Windsor, fronting the road

to Frogmore and Windsor Castle, and this precipitated a policy

of Crown land purchase.

By 1878 there were eight looms and this number had increased

to sixteen by 1884, the same number as at the closure in 1890.

Recalling that there had been 100 households attached to the

manufactory, this amounted to a remarkable total in a village

then of about 1,100 inhabitants but nothing of the French influence

appears to remain, only a faint memory.

Events after The Death

of Prince Leopold

The sudden death of Prince

Leopold on 28 March, 1884, was a great blow to the manufactory.

The Prince had been aware of the difficulties ahead when he drafted

a letter on 21 February 1884. It was designed to enlist the sympathy

and help of Corporations and other public bodies in an effort

to establish a national enterprise connected with the Art Industry,

with aims for training and employment. He was succeeded as President

by his brother, the Prince of Wales, who circulated a similar

letter dated 22 May 1884 expressing a desire to second the efforts

made by Prince Leopold, and inviting donations towards the Endowment

Fund, orders for tapestries, and for the repair of old tapestries.

Resulting donations appear to have been few and the only order

of note was from the City of London for four historical tapestries

which now hang in the Mansion House. An order for the repair

of tapestries from Hampton Court Palace was actively opposed,

because the financial position of the manufactory was giving

cause for alarm, and, very reasonably, for the Prince of Wales

to be seen as the President of a bankrupt manufactory could not

be viewed with anything but alarm by many.

Largely due, however, to persistent efforts by the Secretary,

Sir Robert Collins and by Princess Helen, Duchess of Albany (the

widow of Prince Leopold) and to the sympathy of Queen Victoria,

the manufactory was saved from immediate closure. Control was

vested in the hands of the Guarantors who had put their money

into the project and they decided to continue operations in the

face of opposition from many at court. The Guarantors still had

some hope of getting their money back when the stocks had been

sold, particularly if new orders could be obtained. The Gibbs

family ordered two groups of historical tapestries, 'The Windsor

Tapestries at Tyntesfield Somerset' and the 'Windsor Tapestries

at Aldenham House Hertfordshire', which were described in detail

by the designer Herbert Bone in privately printed pamphlets dated

1888 and 1881 respectively. The reputation of the Manufactory

gained much from these magnificent tapestries according to contemporary

reports but only the former have been traced and seen by the

writer, although the latter group may exist still - they

passed through the London auction salerooms in the 1930s.

After these orders and a few others had been completed, the decline

of the Windsor Manufactory could not be arrested. Henri C. J.

Henry made great efforts in 1888 to secure an order from the

Drapers Company for a copy of 'Jason and Medea', the 18th century

Gobelin tapestry in the Grand Reception Room at Windsor Castle.

The order seemed imminent and consent to make the copy had been

received, when the Drapers changed their minds. Whether the works

at Old Windsor had appeared run down when visited by the Company's

representatives (certainly many workers had drifted back to France

by then) or whether pressure had been exerted is not known. The

long hoped for help from the Government in the form of the creation

of a National Establishment (as in France) to make and repair

fine tapestries for the nation's public buildings was not to

become fact and after more than twelve years all those concerned

must have lost heart. The £1,000 or so a year grant for

'The Arts' that had stopped because of Government economies after

the Prince Consort died was not to be recommended but it was

dourly noted by the Guarantors that large sums were spent on

buying foreign 'works of art' to embellish Government buildings.

Some newspaper reviews of the fine tapestries, while praising

their artistry and quality referred to their alleged unhygienic

properties. A series of bad harvests in the late 1870s followed

by a huge increase in food imports including prairie wheat and

New Zealand frozen mutton spelt ruin for British agriculture

and less money for the great landowners whose orders might have

kept the works open. By September 1888 the last French weaver,

except for Brignolas, had returned to Aubusson. Some were to

be persuaded to go

to New York, as did the Foussadier family of five, apparently

direct from Aubusson early in 1893. William Baumgarten's inducements

of good wages and steady employment had won their favour and

the first American tapestry works was to start by the Bronx river.

Brignolas moved to Poland Street, Soho, where he set up his workshop.

Among his works there is a series depicting the history of the

Clan Macintosh.

The Old Windsor Manufactory closed its doors on Christmas Eve

1890. The plant was sold by auction in March 1895. It included

sixteen looms, three spinning wheels, a French billiards table,

100 lots of household furniture and the magnificent cartoons

by British artists including E. M. Ward R.A. Almost all of these

were bought by manufacturers from Aubusson for ridiculously low

prices - 'hardly more than the value of the paper canvas and

string' reported the press. Some 'false' Royal Windsor tapestries

were to come on to the market, giving the Manufactory a bad name

but whether or not these came from Aubusson is not known. They

look like 'RWTs', but have no marks.

Exhibitions and Collections

The fame of the Royal Windsor

Tapestry Manufactory may be traceable to an Exposition promoted

in the Golden Gate Park, San Francisco in 1894 by M. H. de Young

who is known to have been impressed by the World's Columbian

Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, and it was to the Chicago Fair

of 1893 that Walter Henry Harris of the City of London, British

Commissioner to the Fair, took a collection of 31 Royal Windsor

Tapestries. He had them photographed in 'platinotype' and the

prints bound together with a preface outlining the history of

the Manufactory in four copies. He was permitted to present the

first of these to Queen Victoria at Balmoral, the second to the

Duchess of Albany and the third to the Prince of Wales. The last

copy appears to be lost, but the other two are in the Royal Collection

and Princess Alice's residence at Kensington Palace respectively,

while the fourth is in the Reading Reference Library.

The San Francisco Exposition of 1894 left a dollar surplus and

the exhibited items. The latter became the nucleus of the M.

H. de Young Memorial Museum at Golden Gate Park, San Francisco,

and also contributed to the equally magnificent California Palace

of the Legion of Honor at Lincoln Park. The collection of tapestries

augmented by gifts from the Hearst Foundation and other important

gifts and purchases has resulted in a concentration of famous

tapestries probably unrivalled anywhere in the world, as demonstrated

by their 'Five Centuries of Tapestry' exhibition of 1976.

The RWTM Weavers Mark

Royal Windsor Tapestries

may be identified by the weaver's mark, which is a stylized crown

above two capital 'L', the first reversed.

The Royal Windsor

Tapestry weavers mark

The Royal Windsor

Tapestry weavers mark

N.B. For

simplicity in these pages '

_l l_ ' has been used in the accompanying text pages

This is usually found on

the top guard edge, sometimes with 'Royal Windsor Tapestry' woven

in block letters about one inch in height. In the early tapestries,

the weavers' marks were superimposed on the design, near the

bottom, as in 'The Merry Wives of Windsor' series.

When King Edward came to deal with the personal possessions left

at Windsor Castle by Queen Victoria, it appears that tapestries

which had been rolled up and forgotten were among other things

disposed of or destroyed.

No details have survived concerning the complete output of the

manufactory, but the items on this web site comprise almost every

item found to date and is sufficient perhaps to indicate the

importance of the Old Windsor tapestries: the only attempt other

than that of William Morris to revive this ancient craft in England

in the 19th century.

Index to the

Tapestries

The Royal

Windsor History Zone

The Royal

Windsor Home Page

ALSO SEE (External

Link)

Tapestries Direct

More about the History of Tapestry

To contact us,

email Thamesweb.

To contact us,

email Thamesweb.

|